A Feature Preprocessing Workflow

How I deal with wide datasets when building a predictive model

Introduction

In this post, I will describe a preprocessing workflow that I use whenever I have a lot of variables (wide data) and need to build a predictive model quickly.

The workflow has three stages:

- Univariate feature selection using the {Information} package

- Feature engineering using the {vtreat} package

- Removal of redundant features using the {caret} package

The overall goal of the approach described here is to provide a reasonable number of highly relevent and non-redundant inputs to tree-based classification algorithms, such as random forests or gradient boosting machines.

To show how it works, let’s start by loading the necessary packages, and then get some example data.

# load packages

library(dplyr)

library(Information)

library(rsample)

library(caret)

library(tidyselect)

library(vtreat)

library(stringr)

Example data

I will use a dataset from the {Information} package to illustrate the

workflow (actually two datasets, one called train and the other called

valid). The data represent a marketing campaign with a treat-control

design.

If we limit the dataset to the treat group, that gives us >10,000

records and 70 variables. The response variable purchase is 1 or 0

depending on whether the customer made a purchase or not. The predictors

are mainly credit bureau variables.

Since the dataset is clean (all numeric), I’m going to dirty it up a bit

by making unique_id a character variable, and grouping the d_region

indicators into one character variable with 4 values.

# get example datasets

df1 <- Information::train

df2 <- Information::valid

# combine and dirty up

df <- df1 %>%

bind_rows(df2) %>%

rename_with(~str_to_lower(.)) %>%

filter(treatment == 1) %>%

select(-treatment) %>%

mutate(

unique_id = as.character(unique_id),

d_region = case_when(

d_region_a == 1 ~ "a",

d_region_b == 1 ~"b",

d_region_c == 1 ~ "c",

TRUE ~ "d"

)

) %>%

select(-c("d_region_a", "d_region_b", "d_region_c"))

rm(list = c("df1", "df2"))

Data partitioning

Avoid using the same data for feature preprocessing and model training as this could result in nested model bias. Instead, do a three-way split. For example, I will use 60% of the example data for model training, 20% for feature preprocessing, and 20% for testing. See this article for more information about nested model bias and how to avoid it.

set.seed(12345)

# split train vs. the rest

split1 <- initial_split(df, 0.6, strata = purchase)

df_train <- training(split1)

df_split2 <- testing(split1)

# split preprocessing vs. test

split2 <- initial_split(df_split2, 0.5, strata = purchase)

df_pre <- training(split2)

df_test <- testing(split2)

rm(list = c("df", "df_split2", "split1", "split2"))

Check to make the sure the split worked properly by seeing if the response variable mean is the same between samples.

tibble(

pre = mean(df_pre$purchase),

train = mean(df_train$purchase),

test = mean(df_test$purchase)

)

## # A tibble: 1 x 3

## pre train test

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 0.201 0.201 0.201

Information value

Information value (IV) is a highly flexible approach that lets you measure the strength of association betweeen the response and each predictor. It’s a good way to filter out irrelevant variables prior to building a model.

There are several advantages of IV over other filtering methods.

- IV can detect linear and non-linear relationships

- IV scores allow you to directly compare continuous and categorical variables

- IV can handle missing data without imputation and assess the predictive power of NAs

It is good practice to split the preprocessing dataset prior to estimating IV. This allows you to adjust the IV estimates using cross-validation to prevent weak predictors from getting past the filter by chance. See the {Information} package vignette for more details.

set.seed(666)

# split preprocessing data

iv_split <- initial_split(df_pre, 0.5, strata = "purchase")

df_iv_train <- training(iv_split)

df_iv_test <- testing(iv_split)

# calculate IV

iv <- create_infotables(

data = df_iv_train,

valid = df_iv_test,

y = "purchase"

)

Note that the unique_id variable was ignored because it has too many

levels. This is a handy feature of the {Information} package when

dealing with large datasets. It automatically ignores “junk” variables,

like customer IDs and zip codes. Any feature that’s non-numeric with

more than 1,000 levels gets excluded.

The create_infotables() function will create a data frame (accessible

via iv$Summary) with an IV estimate for each predictor, along with a

cross-validation penalty, and the adjusted IV score.

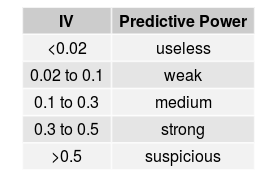

Once you have the IV estimates, you will need to pick a threshold for excluding variables based on adjusted IV. This is subjective. But in general, the rule of thumb is:

You don’t want to be too restrictive at this stage, especially if

you are using a modeling approach that has a built-in feature selection

process, as is the case with tree-based algorithms. Typically, I would

drop all variables with adjusted IV <0.02. However, if most of the

variables have relatively low IV scores, I would take the top_n() and

hope for the best.

# get top predictors

top_iv <- iv$Summary %>%

filter(AdjIV > 0.02)

# save predictor names for filtering

top_nm <- as.character(top_iv$Variable)

top_iv

## Variable IV PENALTY AdjIV

## 1 n_open_rev_acts 0.78808585 0.071311360 0.71677449

## 2 tot_hi_crdt_crdt_lmt 0.83245714 0.117402471 0.71505467

## 3 ratio_bal_to_hi_crdt 0.65154998 0.116854610 0.53469537

## 4 m_snc_oldst_retail_act_opn 0.57731695 0.089622002 0.48769495

## 5 d_na_m_snc_mst_rcnt_act_opn 0.41328900 0.024885205 0.38840379

## 6 m_snc_mst_rcnt_act_opn 0.50501697 0.166593270 0.33842370

## 7 hi_retail_crdt_lmt 0.41075125 0.102026928 0.30872432

## 8 avg_bal_all_prm_bc_acts 0.35052146 0.063045819 0.28747564

## 9 ratio_retail_bal2hi_crdt 0.34148718 0.055783357 0.28570382

## 10 n_of_satisfy_fnc_rev_acts 0.30889636 0.041741804 0.26715456

## 11 d_na_avg_bal_all_fnc_rev_acts 0.25496525 0.021389665 0.23357559

## 12 prcnt_of_acts_never_dlqnt 0.33429544 0.103424077 0.23087136

## 13 avg_bal_all_fnc_rev_acts 0.25673030 0.033986232 0.22274407

## 14 n_fnc_acts_vrfy_in_12m 0.22964383 0.063106470 0.16653736

## 15 n_fnc_instlacts 0.16350030 0.040834858 0.12266544

## 16 student_hi_cred_range 0.12048557 0.002198665 0.11828690

## 17 d_region 0.15013706 0.035344772 0.11479229

## 18 n_bc_acts_opn_in_24m 0.13566094 0.032034754 0.10362618

## 19 m_snc_mstrec_instl_trd_opn 0.15369658 0.058175939 0.09552064

## 20 d_na_m_snc_oldst_mrtg_act_opn 0.10629282 0.027184149 0.07910867

## 21 m_snc_oldst_mrtg_act_opn 0.11175094 0.033558786 0.07819215

## 22 n_bc_acts_opn_in_12m 0.10175870 0.033978431 0.06778027

## 23 tot_othrfin_hicrdt_crdtlmt 0.07942734 0.011989605 0.06743773

## 24 n_pub_rec_act_line_derogs 0.10838429 0.047075686 0.06130861

## 25 agrgt_bal_all_xcld_mrtg 0.11818141 0.061217651 0.05696376

## 26 ratio_prsnl_fnc_bal2hicrdt 0.06122417 0.012688651 0.04853552

## 27 m_snc_mstrcnt_mrtg_act_upd 0.05714766 0.011182831 0.04596483

## 28 n_satisfy_prsnl_fnc_acts 0.04345530 0.002040935 0.04141436

## 29 n_bank_instlacts 0.09145097 0.053917161 0.03753381

## 30 n_30d_and_60d_ratings 0.04249370 0.007780171 0.03471353

## 31 tot_instl_hi_crdt_crdt_lmt 0.04437595 0.012048230 0.03232772

## 32 n_disputed_acts 0.04227185 0.010734430 0.03153742

## 33 d_na_m_sncoldst_bnkinstl_actopn 0.04751751 0.024308098 0.02320941

## 34 n_30d_ratings 0.05123535 0.028309813 0.02292553

## 35 d_na_ratio_prsnl_fnc_bal2hicrdt 0.02369415 0.001193081 0.02250107

## 36 n_satisfy_instl_acts 0.06611851 0.044733739 0.02138477

## 37 n30d_orwrs_rtng_mrtg_acts 0.02693511 0.005762157 0.02117296

## 38 n_inquiries 0.03130803 0.010250884 0.02105715

## 39 n_retail_acts_opn_in_24m 0.07007429 0.049037889 0.02103640

## 40 n_fnc_acts_opn_in_12m 0.03202549 0.011258903 0.02076659

## 41 n_satisfy_oil_nationl_acts 0.03283909 0.012552947 0.02028614

As you can see, filtering by adjusted IV reduces the number of predictors in our example dataset to 41. That implies that 37% of the original 65 predictors where probably “useless.”

Feature engineering

{vtreat} is my go-to R package for common feature engineering tasks. For a formal description of the package read this paper. The package is also described in the excellent book Practical Data Science with R by the package authors Nina Zumel and John Mount.

The {vtreat} package has functions that will automatically:

- Replace NAs with the column mean value (numeric) or majority class (non-numeric)

- Create missing-indicator variables

- Dummy code all non-numeric variables with frequency >2% (rare levels get grouped together)

- Truncate numeric distributions to mitigate outliers

- Create derived versions of non-numeric variables using prevalance coding and impact coding

Prevalence coding replaces the levels of a categorical variable with the proportion each level is observed in the dataset. Impact coding uses the marginal effect from a single-variable logistic regression as a replacement for each level in a categorical variable. Both derived variables are numeric.

Create treatment plan

Use the designTreatmentsC() function to create a variable treatment

plan for classification models. There are a lot of arguments for this

function, so check the documentation. Save the treatment plan

(vtreat_plan) as an .RDS object so you can apply it to non-training

data prior to generating model predictions.

# filter preprocessing data by IV

df_vtreat <- df_pre %>%

select(all_of(top_nm), purchase)

# create plan

vtreat_plan <- designTreatmentsC(

dframe = df_vtreat,

varlist = top_nm,

outcomename = "purchase",

outcometarget = 1,

collarProb = .025

)

## [1] "vtreat 1.6.0 inspecting inputs Thu Jul 9 16:31:02 2020"

## [1] "designing treatments Thu Jul 9 16:31:02 2020"

## [1] " have initial level statistics Thu Jul 9 16:31:02 2020"

## [1] " scoring treatments Thu Jul 9 16:31:02 2020"

## [1] "have treatment plan Thu Jul 9 16:31:02 2020"

## [1] "rescoring complex variables Thu Jul 9 16:31:02 2020"

## [1] "done rescoring complex variables Thu Jul 9 16:31:03 2020"

Prepare training data

After you have the treatment plan object, you can apply it to a new

dataset using prepare(). This creates a new data frame with treated

variables based on the codeRestriction argument. Read

this vignette

for a description of the different {vtreat} variable types.

# create treated data frame

df_train2 <- prepare(

treatmentplan = vtreat_plan,

dframe = df_train,

codeRestriction = c("clean", "lev", "catB", "catP", "isBAD"),

doCollar = TRUE

)

Explore derived variables

# check the d_region variable

df_train2 %>%

select(contains("d_region")) %>%

head()

## d_region_catP d_region_catB d_region_lev_x_a d_region_lev_x_b

## 1 0.3105683 -0.53748855 1 0

## 2 0.2592223 0.53943640 0 0

## 3 0.3105683 -0.53748855 1 0

## 4 0.3105683 -0.53748855 1 0

## 5 0.3105683 -0.53748855 1 0

## 6 0.1884347 -0.08657372 0 1

## d_region_lev_x_c d_region_lev_x_d

## 1 0 0

## 2 0 1

## 3 0 0

## 4 0 0

## 5 0 0

## 6 0 0

Notice that the original d_region character variable has been

transformed into 4 dummy indicators, plus 2 derived variables based on

prevalence (“catP”) and impact coding (“catB”). The prepare() function

will do this automatically for every non-numeric variable in the

dataset.

Remove redundant variables

Redundant variables are predictors that are highly correlated with one or more other predictors in the dataset.

From a predictive accuracy standpoint, it is not strictly necessary to remove redundant variables prior to model fitting. This is one of the many distinctions between predictive and explanatory modeling.

However, when using tree-based algorithms, it is helpful to remove redundant predictors in order to get more accurate variable importance rankings. To find the most redudant features in a dataset, I use the findCorrelation() function from the {Caret} package.

# get names of redundant predictors

corr_vars <- findCorrelation(

cor(

df_train2,

method = "spearman"

),

cutoff = 0.9,

names = TRUE,

exact = TRUE

)

corr_vars

## [1] "tot_instl_hi_crdt_crdt_lmt" "n_bank_instlacts"

## [3] "n_30d_ratings"

And voila…

# filter out redundant predictors

df_train3 <- df_train2 %>% select(-all_of(corr_vars))

str(df_train3)

## 'data.frame': 6020 obs. of 44 variables:

## $ n_open_rev_acts : num 2 1 6 1 0 18 0 6 1 1 ...

## $ tot_hi_crdt_crdt_lmt : num 24300 11500 33600 200 0 ...

## $ ratio_bal_to_hi_crdt : num 5 0 0.4 0 36.1 ...

## $ m_snc_oldst_retail_act_opn : num 164 164 71 367 164 ...

## $ d_na_m_snc_mst_rcnt_act_opn : num 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ m_snc_mst_rcnt_act_opn : num 92 23 9 161.8 29.9 ...

## $ hi_retail_crdt_lmt : num 0 0 600 200 0 400 0 3000 400 0 ...

## $ avg_bal_all_prm_bc_acts : num 607 0 61 2494 2494 ...

## $ ratio_retail_bal2hi_crdt : num 11.5 11.5 0 0 11.5 ...

## $ n_of_satisfy_fnc_rev_acts : num 0 0 0 0 0 3 0 1 0 0 ...

## $ d_na_avg_bal_all_fnc_rev_acts : num 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 ...

## $ prcnt_of_acts_never_dlqnt : num 100 100 100 100 80.8 ...

## $ avg_bal_all_fnc_rev_acts : num 1767 1767 1767 1767 1767 ...

## $ n_fnc_acts_vrfy_in_12m : num 0 0 0 0 0 3 0 0 0 3 ...

## $ n_fnc_instlacts : num 1 0 0 0 0 2 0 1 0 5 ...

## $ student_hi_cred_range : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ d_region_catP : num 0.311 0.259 0.311 0.311 0.311 ...

## $ d_region_catB : num -0.537 0.539 -0.537 -0.537 -0.537 ...

## $ n_bc_acts_opn_in_24m : num 0 1 1 0 0 2 0 1 0 1 ...

## $ m_snc_mstrec_instl_trd_opn : num 126.9 41.8 41.8 41.8 41.8 ...

## $ d_na_m_snc_oldst_mrtg_act_opn : num 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 ...

## $ m_snc_oldst_mrtg_act_opn : num 139 139 139 139 139 ...

## $ n_bc_acts_opn_in_12m : num 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 ...

## $ tot_othrfin_hicrdt_crdtlmt : num 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ n_pub_rec_act_line_derogs : num 0 0 0 0 2 0 2 0 0 5 ...

## $ agrgt_bal_all_xcld_mrtg : num 1214 0 122 0 0 ...

## $ ratio_prsnl_fnc_bal2hicrdt : num 51.7 51.7 51.7 51.7 51.7 ...

## $ m_snc_mstrcnt_mrtg_act_upd : num 0.665 0.665 0.665 0.665 0.665 ...

## $ n_satisfy_prsnl_fnc_acts : num 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 ...

## $ n_30d_and_60d_ratings : num 0 0 0 0 0 5 0 0 0 16 ...

## $ n_disputed_acts : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ d_na_m_sncoldst_bnkinstl_actopn: num 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...

## $ d_na_ratio_prsnl_fnc_bal2hicrdt: num 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 ...

## $ n_satisfy_instl_acts : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 ...

## $ n30d_orwrs_rtng_mrtg_acts : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 8 ...

## $ n_inquiries : num 0 0 1 0 4 1 2 0 0 16 ...

## $ n_retail_acts_opn_in_24m : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ n_fnc_acts_opn_in_12m : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ n_satisfy_oil_nationl_acts : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ d_region_lev_x_a : num 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 ...

## $ d_region_lev_x_b : num 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ d_region_lev_x_c : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ d_region_lev_x_d : num 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 ...

## $ purchase : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

After filtering by IV, treating with {vtreat}, and removing 3 redundant variables, the final dataset has 43 predictors that are all numeric and ready for model training.

Conclusion

The preprocessing workflow described here works well for the sorts of modeling projects I work on because it’s basically an excercie in data mining. But if you have a relatively small set of well-understood predictors, the methods for variable selection and data reduction described in Frank Harrell’s book Regression Modeling Strategies might be more appropriate. Also, to take your preprocessing workflow to the next level, consider using the tidymodels package {recipes}.

Questions or comments?

Feel free to reach out to me at any of the social links below.

For more R content, please visit R-bloggers and RWeekly.org.